For generations, if your aortic valve stopped working properly, there was only one way forward: open-heart surgery.

A major chest incision. The heart temporarily stopped. Weeks—or even months—of recovery.

For many older or fragile patients, this wasn’t just daunting—it was downright dangerous.

But over the past decade, a quiet revolution has been reshaping how cardiologists treat aortic stenosis. The procedure?

Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement (TAVR) — a minimally invasive way to replace a damaged valve without opening the chest.

What was once offered only to the sickest, highest-risk patients is now saving lives across age groups, shortening recovery times, and making heart valve replacement far less intimidating.

This guide dives deep into what TAVR is, why it matters, who it’s for, how it’s done, and how it stacks up against open-heart surgery—with insights from cardiology experts and real-world patient experiences.

Understanding the Aortic Valve and Its Importance

The heart has four valves, but the aortic valve plays one of the most critical roles—it controls blood flow from the heart’s left ventricle into the aorta, the main artery that carries oxygen-rich blood to the rest of your body.

When the aortic valve becomes stiff or narrowed—a condition called aortic stenosis—blood flow is restricted. This forces the heart to work harder, eventually weakening the heart muscle.

Common symptoms of severe aortic stenosis include:

-

Chest pain or pressure

-

Shortness of breath, even with light activity

-

Fainting spells (syncope)

-

Extreme fatigue

-

Swelling in the legs and ankles

If left untreated, severe aortic stenosis is life-threatening. Studies show that once symptoms develop, average survival without treatment is just 2–3 years.

Traditional Treatment: Open-Heart Surgery

Historically, the gold standard treatment for severe aortic stenosis was Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement (SAVR).

In SAVR, the surgeon opens the chest, stops the heart, removes the diseased valve, and replaces it with a mechanical or biological prosthetic valve.

While highly effective, SAVR has some significant drawbacks:

-

Invasiveness – Large chest incision and splitting of the breastbone

-

Long recovery – Hospital stays of 1–2 weeks, with months of rehabilitation

-

Higher risk for elderly or frail patients – Complications such as infections, stroke, and kidney injury are more likely

-

Emotional burden – The thought of “open-heart” surgery can be overwhelming

For younger, healthier patients, these risks are acceptable because surgical valves have excellent long-term durability. But for many elderly patients, SAVR is simply too risky.

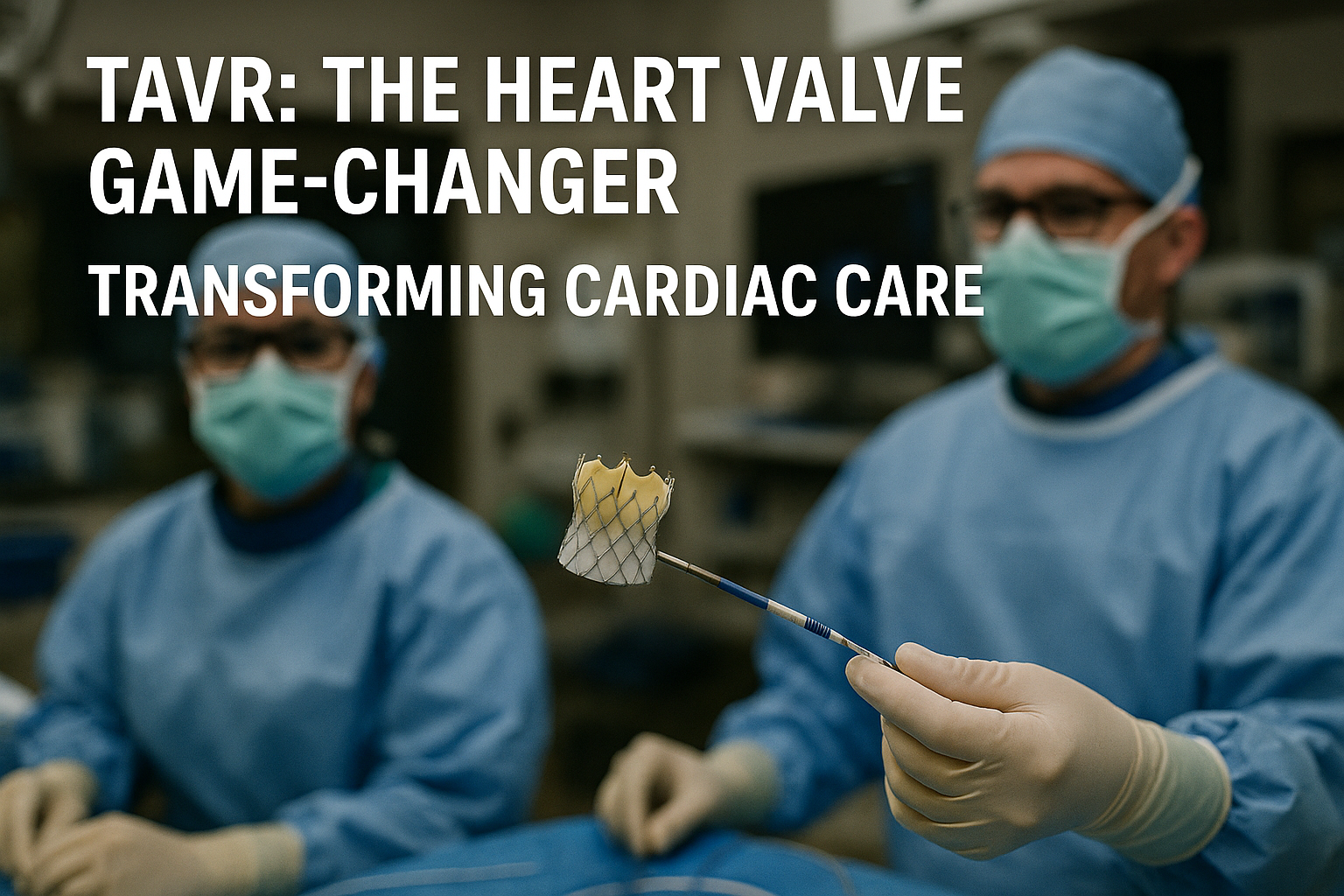

Enter TAVR: A Revolutionary Alternative

Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement offers the same end goal—replacing the damaged valve—but through an entirely different approach.

Instead of opening the chest, doctors insert a thin catheter—usually through the femoral artery in the groin. The catheter carries a collapsible replacement valve to the heart. Once positioned inside the diseased valve:

-

The new valve is expanded (either with a balloon or self-expanding frame)

-

It pushes the old valve leaflets aside

-

It starts working immediately, restoring normal blood flow

Key differences from open-heart surgery:

-

No large incision

-

No need to stop the heart

-

Often no need for general anesthesia

-

Hospital stay is usually just a few days

Why TAVR Is Changing the Game

The beauty of TAVR lies in its minimally invasive nature—reducing trauma, risk, and recovery time. What’s more, studies have shown that for many high-risk patients, TAVR is just as effective as surgery in improving survival and quality of life.

In fact, landmark trials such as PARTNER 3 and Evolut Low Risk have even found TAVR to be non-inferior or superior to surgery in certain low- and intermediate-risk patients.

Who Is an Ideal Candidate for TAVR?

While cardiologists now consider TAVR for a broader range of patients, the most clear-cut candidates are:

1. Elderly Patients (Over 70–75 years)

Older adults often face higher surgical risks due to age-related frailty. For them, TAVR offers a safer alternative with fewer complications and faster recovery.

2. Patients with Multiple Medical Conditions

Conditions like chronic lung disease, kidney problems, or previous heart surgeries can make open-heart surgery too dangerous. TAVR is often the best choice.

3. Patients Deemed “Inoperable”

Some individuals are told surgery is simply not an option. TAVR gives these patients a lifeline.

4. Those with Severe Anxiety about Surgery

Even if physically fit for surgery, some patients strongly prefer a less invasive option.

5. Selected Younger, Lower-Risk Patients

While surgery is still the default for younger patients due to proven valve durability, TAVR is increasingly considered for those in their 60s who want quicker recovery or have specific anatomical advantages.

Bottom line: The decision is made by a Heart Team—a group of cardiologists, cardiac surgeons, and imaging specialists—tailored to each patient’s health profile and preferences.

TAVR vs. Open-Heart Surgery: Head-to-Head

| Feature | Open-Heart Surgery (SAVR) | TAVR |

|---|---|---|

| Approach | Large chest incision, heart stopped | Catheter through groin/artery |

| Anesthesia | General (always) | Often local with sedation |

| Hospital Stay | 7–14 days | 2–5 days |

| Recovery Time | Weeks to months | Days to weeks |

| Best Candidates | Younger, low-risk patients | Elderly/high-risk or inoperable |

| Durability | 15–20 years | 8–12 years (current data) |

| Complication Risk | Higher in frail/elderly | Lower for high-risk patients |

The TAVR Procedure: Step-by-Step

Here’s what happens during a typical TAVR:

-

Pre-Procedure Workup

-

Echocardiogram and CT scan to measure valve and vessel size

-

Blood tests and ECG

-

Meeting with the Heart Team

-

-

Access Site Preparation

-

Usually the femoral artery in the groin

-

Area cleaned and numbed

-

-

Catheter Insertion

-

A sheath is placed into the artery

-

The catheter with the new valve is advanced to the heart

-

-

Valve Deployment

-

The new valve is positioned inside the diseased valve

-

It is expanded (balloon or self-expanding) to push the old valve aside

-

-

Function Check

-

Imaging confirms correct placement and valve function

-

-

Catheter Removal & Closure

-

Sheath removed, site closed

-

Patient monitored in recovery

-

Duration: 1–2 hours

Hospital Stay: Often 2–3 days

The Benefits of TAVR for Elderly Patients

-

Minimally invasive — no chest opening

-

Lower complication rates — fewer strokes, less bleeding

-

Faster mobility — many walk the same day

-

Shorter hospital stay — reducing infection risk

-

Better quality of life — improved energy and independence

Example:

Mrs. Rao, a 78-year-old with severe aortic stenosis, could barely walk to her mailbox. Her lung disease made open-heart surgery too risky. She underwent TAVR and was back to light gardening within two weeks.

Addressing Common Concerns

1. How Long Will the Valve Last?

Current data show TAVR valves last 8–12 years, with ongoing improvements expected to extend durability.

2. What Are the Risks?

Possible complications include vascular injury, stroke, or mild leakage around the valve—but with experienced operators, rates are low.

3. Is It Covered by Insurance?

Many health systems and insurers now cover TAVR for eligible patients. Generic or cost-reduced valves are making it more affordable.

Cost and Accessibility: Breaking Barriers

One of the biggest breakthroughs is the rise of high-quality generic TAVR valves, often 50–80% cheaper than branded devices. These provide the same safety and performance, making TAVR accessible to more patients—especially in countries where cost is a major barrier.

The Future of TAVR

Research is expanding TAVR’s reach to:

-

Younger patients

-

Bicuspid aortic valves

-

Valve-in-valve procedures for failed surgical valves

The technology is evolving—smaller devices, better durability, and even easier recovery are on the horizon.

Takeaway: TAVR as a Life-Changing Option

For patients once told “there’s nothing we can do,” TAVR is rewriting the ending.

It’s proof that medical innovation isn’t just about saving lives—it’s about giving life back.

If you or a loved one has been diagnosed with severe aortic stenosis, ask your cardiologist about TAVR. The conversation could change everything.